Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (2003 to present)

Rooms of the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum contain thousands of photos taken by the Khmer Rouge of their victims.

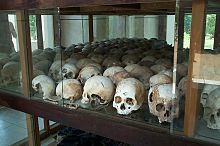

Skulls in the Choeung Ek.

On 6 June 2003 the Cambodian government and the United Nations reached an agreement to set up the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) which would focus exclusively on crimes committed by the most senior Khmer Rouge officials during the period of Khmer Rouge rule of 1975–1979.[73] The judges were sworn in early July 2006.[74][75][76]

The genocide charges related to killings of Cambodia's Vietnamese and Cham minorities, which is estimated to make up tens of thousand killings and possibly more[77][78]

The investigating judges were presented with the names of five possible suspects by the prosecution on 18 July 2007.[74][79]

- Kang Kek Iew was formally charged with war crime and crimes against humanity and detained by the Tribunal on 31 July 2007. He was indicted on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity on 12 August 2008.[80] His appeal against his conviction for war crimes and crimes against humanity was rejected on 3 February 2012, and he is serving a sentence of life imprisonment.[81]

- Nuon Chea, a former prime minister, who was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010. He was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 19 September 2007. His trial started on 27 June 2011[77][82] and ended on 7 August 2014, with a life sentence imposed for crimes against humanity.[83]

- Khieu Samphan, a former head of state, who was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010. He was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 19 September 2007. His trial began on 27 June 2011.[77][82] and also ended on 7 August 2014, with a life sentence imposed for crimes against humanity.[83]

- Ieng Sary, a former foreign minister, who was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010. He was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 12 November 2007. His trial started on 27 June 2011, and ended with his death on 14 March 2013. He was never convicted.[77][82]

- Ieng Thirith, a former minister for social affairs and wife of Ieng Sary, who was indicted on charges of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity and several other crimes under Cambodian law on 15 September 2010. She was transferred into the custody of the ECCC on 12 November 2007. Proceedings against her have been suspended pending a health evaluation.[82][84]

By the International Criminal Court

Since 2002, the International Criminal Court can exercise its jurisdiction if national courts are unwilling or unable to investigate or prosecute genocide, thus being a "court of last resort," leaving the primary responsibility to exercise jurisdiction over alleged criminals to individual states. Due to the United States concerns over the ICC, the United States prefers to continue to use specially convened international tribunals for such investigations and potential prosecutions.[85]Darfur, Sudan

A mother with her sick baby at Abu Shouk IDP camp in North Darfur

In March 2005, the Security Council formally referred the situation in Darfur to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, taking into account the Commission report but without mentioning any specific crimes.[89] Two permanent members of the Security Council, the United States and China, abstained from the vote on the referral resolution.[90] As of his fourth report to the Security Council, the Prosecutor has found "reasonable grounds to believe that the individuals identified [in the UN Security Council Resolution 1593] have committed crimes against humanity and war crimes," but did not find sufficient evidence to prosecute for genocide.[91]

In April 2007, the Judges of the ICC issued arrest warrants against the former Minister of State for the Interior, Ahmad Harun, and a Militia Janjaweed leader, Ali Kushayb, for crimes against humanity and war crimes.[92]

On 14 July 2008, prosecutors at the International Criminal Court (ICC), filed ten charges of war crimes against Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir: three counts of genocide, five of crimes against humanity and two of murder. The ICC's prosecutors claimed that al-Bashir "masterminded and implemented a plan to destroy in substantial part" three tribal groups in Darfur because of their ethnicity.

On 4 March 2009, the ICC issued a warrant of arrest for Omar Al Bashir, President of Sudan as the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber I concluded that his position as head of state does not grant him immunity against prosecution before the ICC. The warrant was for war crimes and crimes against humanity. It did not include the crime of genocide because the majority of the Chamber did not find that the prosecutors had provided enough evidence to include such a charge.[93] Later the decision was changed by the Appeals Panel and after issuing the second decision, charges against Omar al-Bashir include three counts of genocide.[94]

Genocide in history

Naked Soviet POWs held by the Nazis in Mauthausen concentration camp.

"... the murder of at least 3.3 million Soviet POWs is one of the

least-known of modern genocides; there is still no full-length book on

the subject in English." —Adam Jones[95]

Revisionist attempts to challenge or affirm claims of genocide are illegal in some countries. For example, several European countries ban the denial of the Holocaust or the Armenian Genocide, while in Turkey referring to the mass killings of Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians and Maronites as genocides may be prosecuted under Article 301.[96]

William Rubinstein argues that the origin of 20th century genocides can be traced back to the collapse of the elite structure and normal modes of government in parts of Europe following the First World War:

The 'Age of Totalitarianism' included nearly all of the infamous examples of genocide in modern history, headed by the Jewish Holocaust, but also comprising the mass murders and purges of the Communist world, other mass killings carried out by Nazi Germany and its allies, and also the Armenian genocide of 1915. All these slaughters, it is argued here, had a common origin, the collapse of the elite structure and normal modes of government of much of central, eastern and southern Europe as a result of the First World War, without which surely neither Communism nor Fascism would have existed except in the minds of unknown agitators and crackpots.

— William Rubinstein, Genocide: a history[97]

Stages of genocide, influences leading to genocide, and efforts to prevent it

For genocide to happen, there must be certain preconditions. Foremost among them is a national culture that does not place a high value on human life. A totalitarian society, with its assumed superior ideology, is also a precondition for genocidal acts.[98] In addition, members of the dominant society must perceive their potential victims as less than fully human: as "pagans," "savages," "uncouth barbarians," "unbelievers," "effete degenerates," "ritual outlaws," "racial inferiors," "class antagonists," "counterrevolutionaries," and so on.[99] In themselves, these conditions are not enough for the perpetrators to commit genocide. To do that—that is, to commit genocide—the perpetrators need a strong, centralized authority and bureaucratic organization as well as pathological individuals and criminals. Also required is a campaign of vilification and dehumanization of the victims by the perpetrators, who are usually new states or new regimes attempting to impose conformity to a new ideology and its model of society.[98]In 1996 Gregory Stanton, the president of Genocide Watch, presented a briefing paper called "The 8 Stages of Genocide" at the United States Department of State.[101] In it he suggested that genocide develops in eight stages that are "predictable but not inexorable".[101][102]

— M. Hassan Kakar[100]

The Stanton paper was presented to the State Department, shortly after the Rwandan Genocide and much of its analysis is based on why that genocide occurred. The preventative measures suggested, given the briefing paper's original target audience, were those that the United States could implement directly or indirectly by using its influence on other governments.

| Stage | Characteristics | Preventive measures |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Classification |

People are divided into "us and them". | "The main preventive measure at this early stage is to develop universalistic institutions that transcend... divisions." |

| 2. Symbolization |

"When combined with hatred, symbols may be forced upon unwilling members of pariah groups..." | "To combat symbolization, hate symbols can be legally forbidden as can hate speech". |

| 3. Dehumanization |

"One group denies the humanity of the other group. Members of it are equated with animals, vermin, insects, or diseases." | "Local and international leaders should condemn the use of hate speech and make it culturally unacceptable. Leaders who incite genocide should be banned from international travel and have their foreign finances frozen." |

| 4. Organization |

"Genocide is always organized... Special army units or militias are often trained and armed..." | "The U.N. should impose arms embargoes on governments and citizens of countries involved in genocidal massacres, and create commissions to investigate violations" |

| 5. Polarization |

"Hate groups broadcast polarizing propaganda..." | "Prevention may mean security protection for moderate leaders or assistance to human rights groups...Coups d’état by extremists should be opposed by international sanctions." |

| 6. Preparation |

"Victims are identified and separated out because of their ethnic or religious identity..." | "At this stage, a Genocide Emergency must be declared. ..." |

| 7. Extermination |

"It is 'extermination' to the killers because they do not believe their victims to be fully human". | "At this stage, only rapid and overwhelming armed intervention can stop genocide. Real safe areas or refugee escape corridors should be established with heavily armed international protection." |

| 8. Denial |

"The perpetrators... deny that they committed any crimes..." | "The response to denial is punishment by an international tribunal or national courts" |

In a paper for the Social Science Research Council Dirk Moses criticises the Stanton approach concluding:

In view of this rather poor record of ending genocide, the question needs to be asked why the "genocide studies" paradigm cannot predict and prevent genocides with any accuracy and reliability. The paradigm of "genocide studies," as currently constituted in North America in particular, has both strengths and limitations. While the moral fervor and public activism is admirable and salutary, the paradigm appears blind to its own implication in imperial projects that are themselves as much part of the problem as they are part of the solution. The US government called Darfur a genocide to appease domestic lobbies, and because the statement cost it nothing. Darfur will end when it suits the great powers that have a stake in the region.Other authors have focused on the structural conditions leading up to genocide and the psychological and social processes that create an evolution toward genocide. Ervin Staub showed that economic deterioration and political confusion and disorganization were starting points of increasing discrimination and violence in many instances of genocides and mass killing. They lead to scapegoating a group and ideologies that identified that group as an enemy. A history of devaluation of the group that becomes the victim, past violence against the group that becomes the perpetrator leading to psychological wounds, authoritarian cultures and political systems, and the passivity of internal and external witnesses (bystanders) all contribute to the probability that the violence develops into genocide.[105] Intense conflict between groups that is unresolved, becomes intractable and violent can also lead to genocide. The conditions that lead to genocide provide guidance to early prevention, such as humanizing a devalued group, creating ideologies that embrace all groups, and activating bystander responses. There is substantial research to indicate how this can be done, but information is only slowly transformed into action.[106]

— Dirk Moses[104]

Kjell Anderson uses a dichotomistic classification of genocides: "hot genocides, motivated by hate and the victims’ threatening nature, with low-intensity cold genocides, rooted in victims’ supposed inferiority."[107]

See also

- Autogenocide

- Countervalue

- Crimes against humanity

- Cultural genocide

- Death squad

- Dehumanization

- Democide

- Effects of genocide on youth

- Ethnic cleansing

- Ethnic hatred

- Ethnocide

- Extrajudicial killing

- Forced displacement

- Forensic anthropology

- Gendercide

- Genocidal rape

- Genocide education

- Homicide

- Infanticide

- Institutional racism

- Involuntary euthanasia

- Local extinction

- Mass Atrocity crimes

- Mass murder

- Omnicide

- Policide

- Political cleansing of population

- Population growth#Human population growth rate

- Religious cleansing

- Ritualcide

- Social cleansing

- Utilitarian genocide

Research

Notes

- For more complete lists, see List of genocides by death toll or Genocides in history.

References

- p. 9. Anderson, Kjell. (2015) Colonialism and Cold Genocide: The Case of West Papua. Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal Vol. 9: Iss. 2: 9–25.

Further reading

Articles- Christopher R. Browning, "The Two Different Ways of Looking at Nazi Murder" (review of Philippe Sands, East West Street: On the Origins of "Genocide" and "Crimes Against Humanity", Knopf, 425 pp., $32.50; and Christian Gerlach, The Extermination of the European Jews, Cambridge University Press, 508 pp., $29.99 [paper]), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXIII, no. 18 (November 24, 2016), pp. 56–58. Discusses Hersch Lauterpacht's legal concept of "crimes against humanity", contrasted with Rafael Lemkin's legal concept of "genocide". All genocides are crimes against humanity, but not all crimes against humanity are genocides; genocides require a higher standard of proof, as they entail intent to destroy a particular group.

- The Genocide in Darfur is Not What It Seems Christian Science Monitor

- Suharto’s Purge, Indonesia’s Silence. Joshua Oppenheimer for The New York Times, September 29, 2015.

- (in Spanish) Aizenstatd, Najman Alexander. "Origen y Evolución del Concepto de Genocidio". Vol. 25 Revista de Derecho de la Universidad Francisco Marroquín 11 (2007). ISSN 1562-2576 [1]

- No Lessons Learned from the Holocaust? Assessing Risks of Genocide and Political Mass Murder since 1955 American Political Science Review. Vol. 97, No. 1. February 2003.

- (in Spanish) Marco, Jorge. "Genocidio y Genocide Studies: Definiciones y debates", en: Aróstegui, Julio, Marco, Jorge y Gómez Bravo, Gutmaro (coord.): "De Genocidios, Holocaustos, Exterminios...", Hispania Nova, 10 (2012). Véase [2]

- What Really Happened in Rwanda? Christian Davenport and Allan C. Stam.

- Reyntjens, F. (2004). "Rwanda, Ten Years On: From Genocide to Dictatorship." African Affairs 103(411): 177–210.

- Brysk, Alison. 1994. "The Politics of Measurement: The Contested Count of the Disappeared in Argentina." Human Rights Quarterly 16: 676–92.

- Davenport, C. and P. Ball (2002). "Views to a Kill: Exploring the Implications of Source Selection in the Case of Guatemalan State Terror, 1977–1996." Journal of Conflict Resolution 46(3): 427–450.

- Krain, M. (1997). "State-Sponsored Mass Murder: A Study of the Onset and Severity of Genocides and Politicides." Journal of Conflict Resolution 41(3): 331–360.

- Andreopoulos, George J., ed. (1994). Genocide: Conceptual and Historical Dimensions. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3249-6.

- Ball, P., P. Kobrak, and H. Spirer (1999). State Violence in Guatemala, 1960–1996: A Quantitative Reflection. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- Bloxham, Donald & Moses, A. Dirk [editors]: The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. [Interdisciplinary Contributions about Past & Present Genocides]. Oxford University Press, second edition 2013. ISBN 978-0-19-967791-7

- Chalk, Frank; Kurt Jonassohn (1990). The History and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses and Case Studies. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-04446-1.

- Charny, Israel W. (1 December 1999). Encyclopedia of Genocide. ABC-Clio Inc. ISBN 0-87436-928-2.

- Conversi, Daniele (2005). "Genocide, ethnic cleansing, and nationalism". In Delanty, Gerard; Kumar, Krishan. Handbook of Nations and Nationalism. 1. London: Sage Publications. pp. 319–33. ISBN 1-4129-0101-4.

- Corradi, Juan, Patricia Weiss Fagen, and Manuel Antonio Garreton, eds. 1992. Fear at the Edge: State Terror and Resistance in Latin America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Elliot, G. (1972). Twentieth Century Book of the Dead. New York, C. Scribner.

- Esparza, Marcia; Henry R. Huttenbach; Daniel Feierstein, eds. (2011). State Violence and Genocide in Latin America: The Cold War Years (Critical Terrorism Studies). Routledge. ISBN 0415664578.

- Gellately, Robert; Kiernan, Ben (July 2003). The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521527503.

- Goldhagen, Daniel (2009). Worse Than War: Genocide, Eliminationism, and the Ongoing Assault on Humanity. PublicAffairs. p. 672. ISBN 1-58648-769-8.

- Harff, Barbara (August 2003). Early Warning of Communal Conflict and Genocide: Linking Empirical Research to International Responses. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-9840-1.

- Hochschild, Adam (1998). King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-395-75924-2.

- Horowitz, Irving (2001). Taking Lives: Genocide and State Power (5th ed.). Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-7658-0094-2.

- Horvitz, Leslie Alan; Catherwood, Christopher (2011). Encyclopedia of War Crimes & Genocide (Hardcover). 2 (Revised ed.). New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0816080830. ISBN 0816080836

- Jonassohn, Kurt; Karin Björnson (1998). Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-314-6.

- Jones, Adam (2010). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-48619-X.

- Kelly, Michael J. (2005). Nowhere to Hide: Defeat of the Sovereign Immunity Defense for Crimes of Genocide & the Trials of Slobodan Milosevic and Saddam Hussein. Peter Lang. ISBN 0-8204-7835-0.

- Kiernan, Ben (2007). Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10098-1.

- Laban, Alexander (2002). Genocide: An Anthropological Reader. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-22355-X.

- Lemarchand, René (1996). Burundi: Ethnic Conflict and Genocide. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56623-1.

- Lemkin, Raphael (2008). Axis rule in occupied Europe : laws of occupation, analysis of government, proposals for redress. Clark, N.J: Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 978-1-58477-901-8.

- Levene, M. (2005). Genocide in the Age of the Nation State. New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

- MacKinnon, Catharine A. (2006). Are Women Human?: And Other International Dialogues. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-02555-5.

- Lewy, Guenter (2012). Essays on Genocide and Humanitarian Intervention. University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-1-60781-168-8.

- Mamdani, M. (2001). When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda. Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press.

- Power, Samantha (2003). "A Problem from Hell": America and the Age of Genocide. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-054164-4.

- Rosenfeld, Gavriel D. (1999). "The Politics of Uniqueness: Reflections on the Recent Polemical Turn in Holocaust and Genocide Scholarship". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 13 (1): 28–61. doi:10.1093/hgs/13.1.28.

- Rotberg, Robert I.; Thomas G. Weiss (1996). From Massacres to Genocide: The Media, Public Policy, and Humanitarian Crises. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 0-8157-7590-3.

- Rummel, R.J. (1994). Death by Government: Genocide and Mass Murder in the Twentieth Century. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-927-6.

- Sagall, Sabby (2013). Final Solutions: Human Nature, Capitalism and Genocide. Pluto Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-7453-2653-5.

- Sands, Philippe (2016). East West Street : on the origins of "Genocide" and "Crimes Against Humanity". New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-385-35071-6.

- Schabas, William A. (2009). Genocide in International Law: The Crime of Crimes (second edition). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-171900-1.

- Schmid, A. P. (1991). Repression, State Terrorism, and Genocide: Conceptual Clarifications. State Organized Terror: The Case of Violent Internal Repression. P. T. Bushnell. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. 312 p.

- Shaw, Martin (2007). What is Genocide?. Cambridge: Polity Press. ISBN 0-7456-3182-7.

- Staub, Ervin (1989). The roots of evil: The origins of genocide and other group violence. New York: Cambridge University Press. 978-0521-42214-7

- Staub, Ervin (2011). Overcoming Evil: Genocide, violent conflict and terrorism. New York: Oxford University Press. 978-0-19-538204-4

- Sunga, Lyal S. (1997). The Emerging System of International Criminal Law: Developments in Codification and Implementation. Kluwer. ISBN 90-411-0472-0.

- Sunga, Lyal S. (1992). Individual Responsibility in International Law for Serious Human Rights Violations. Springer. ISBN 0-7923-1453-0.

- Tams, Christian J.; Berster, Lars; Schiffbauer, Björn (2014). Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide: A Commentary. Munich: C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-60317-4.

- Totten, Samuel; William S. Parsons; Israel W. Charny (2008). Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts (3rd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-99085-8.

- Valentino, Benjamin A. (2004). Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the 20th Century. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3965-5.

- Van den Berghe, P. L. (1990). State Violence and Ethnicity. Niwot, Colo., University of Colorado Press.

- Weitz, Eric D. (2003). A Century of Genocide: Utopias of Race and Nation. Princeton University Press. p. 360. ISBN 0-691-12271-7.

- Schabas, William A. (2006). Preventing Genocide and Mass Killing: The Challenge for the United Nations (PDF). London: Minority Rights Group International. ISBN 1-904584-37-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2007.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Genocide |

| Look up genocide in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Genocide. |

- Voices of the Holocaust—a learning resource at the British Library

- Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948) – full text of Genocide Convention

- Whitaker Report

- 8 Stages of Genocide" by Gregory H. Stanton

- Institute for the Study of Genocide

- International Association of Genocide Scholars

- International Network of Genocide Scholars (INoGS)

- United to End Genocide (merger of Save Darfur Coalition and the Genocide Intervention Network)

- Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Auschwitz Institute for Peace and Reconciliation

- Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

- Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Minnesota

- Genocide Studies Program at Yale University

- Montreal Institute for Genocide Studies at Concordia University

- Minorities at Risk Project at the University of Maryland

- Budapest Centre for Mass Atrocities Prevention

Lemkin's memoirs detail early exposure to the history of Ottoman attacks against Armenians (which most scholars believe constitute genocide), antisemitic pogroms, and other histories of group-targeted violence as key to forming his beliefs about the need for legal protection of groups.

No comments:

Post a Comment